OpenStreetMap in Humanitarian Response

The following story was written by Lena Kang, GDPC Knowledge Management Intern, based on the learning events and discussions at the inaugural HOT Summit, hosted by the American Red Cross.

HOT’s evolving role in humanitarian response

At last week’s inaugural Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) Summit, dozens of humanitarians, geographers, programmers, community builders, and volunteer mappers from around the world gathered to learn and share ideas about the use of OpenStreetMap (OSM) in humanitarian response. Through workshops, presentations, and panel discussions, the event focused on ways in which HOT stands in the juncture between technology and development, governance and partnerships, and education and capacity building in vulnerable and disaster-prone areas.

In his opening remarks, Dr. Lee Schwartz, Geographer of the United States at the Department of State (DoS), discussed the government’s working relationship with HOT and the present-day challenges of digital diplomacy. In doing so, he addressed the continuing need to i) bridge technology and humanitarian response, ii) mainstream human geography in government functions, and iii) foster a wider community of volunteer mappers. In his remarks, he contended that more can be done to mitigate conflicts and disasters by understanding people, societies, and cultures. Dr. Schwartz highlighted the need to invest more in mapping and collecting information on socio-cultural features, in addition to geophysical resources. By “building a satellite of human geography,” this type of investment would produce targeted data essential for understanding key dynamics between people and structures in times of crises.

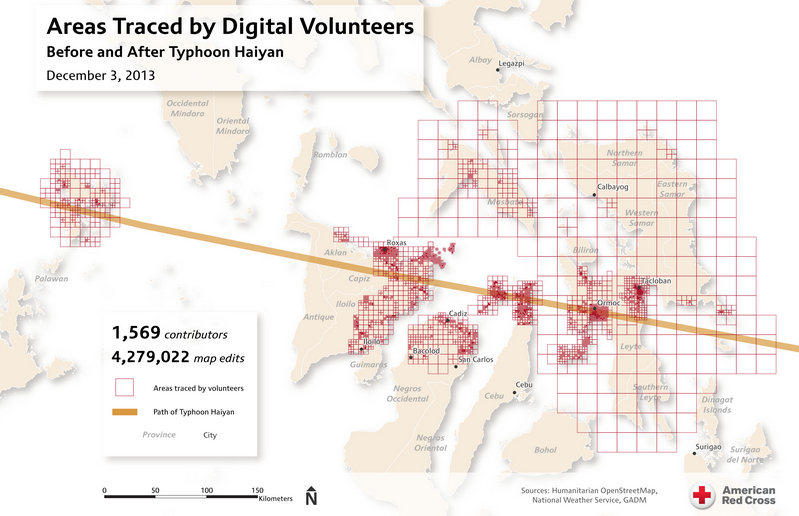

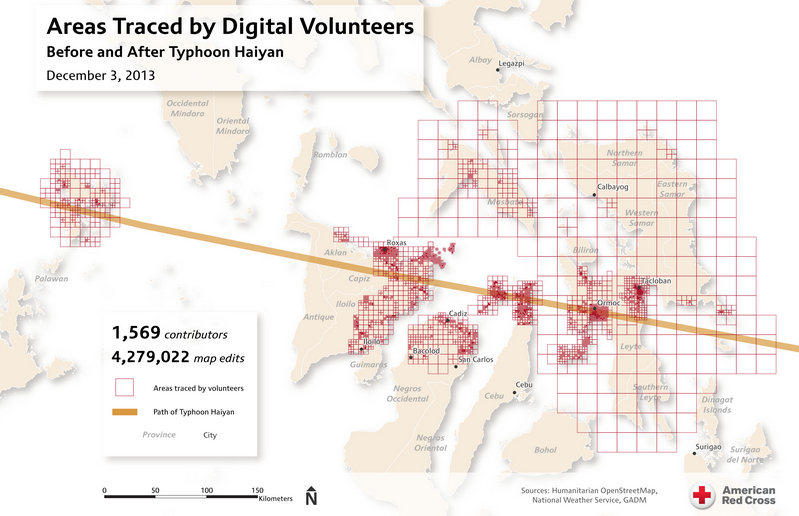

This map helps illustrate the impressive effort by digital volunteers to create base map data within OpenStreetMap in response to typhoon Haiyan. Source: American Red Cross

Humanitarian organizations operating in crisis environments are increasingly utilizing and feeling the power of the crowd. The ever-growing HOT community has made significant contributions in creating real-time maps, which agencies have used for a growing list of humanitarian missions, like combating the cholera outbreak in Haiti, tracking refugee movements in the Horn of Africa, and facilitating aid delivery after Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Five days after the 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit Nepal on the morning of 25 April 2015, over 3400 volunteer mappers had contributed 4.5 million edits via OSM to support the international humanitarian response. As of March 2015, HOT has grown to feature over 800 publicly visible projects, with 5000 registered contributors and 50 million map edits.

Volunteerism and community engagement

In his overview of HOT history, Mikel Maron from the Humanitarian Information Unit (HIU) at the DoS addressed three premises underlying the growth and mobilization of the global HOT community. First, communities and individuals have an overwhelming impulse to help when people are suffering. Second, globalization and social media foster a powerful immediacy to global events. Third, access to and dissemination of information is easier than ever. Within this context, HOT stands to bridge the grassroots OSM community to traditional responders by filling in the missing gaps of information. More than ever, responders have quicker access to contextual awareness which enables improved coordination and resource allocation.

HOT projects and mapping parties around the world are functioning as important catalysts for volunteer engagement. The aggregate contribution of individual volunteers is changing the work of traditional humanitarian response. However, in the enthusiastic and active efforts of global mappers to support a cause, Dr. Schwartz emphasized that more data does not necessarily equate to better data. Rather, “correct and quality information” will always trump quantity. He referenced the 2010 Haiti earthquake response which showed that high volumes of “cluttered, unmanaged information that cannot be prioritized can prevent effective and efficient decision-making.” Moreover, beginners often face technical barriers to entry due to the specialist tools and concepts in mapping. These issues can raise concerns related to data accuracy and validation. Much of the collaborative discussions at the summit revolved around how to engage more inexperienced volunteers through training while professionalizing the work through improvements and innovation.

HOT mapping parties typically provide technical instructions and introduce learners to the OSM Tasking Manager, which facilitates the distribution of tasks, marks areas for validation, and manages the overall progress and homogeneity of the work. Grassroots organizations like Maptime exist for the explicit purpose of outreaching to beginners and creating a safe space to provide them with intentional educational support. Lyzi Diamond, co-founder of Maptime, understands the hesitance of prospective mappers: “Teaching and learning OSM can be difficult. OSM has its own language and a huge ecosystem with tons of use case. It’s no surprise that the OSM community can be daunting for beginners.” By focusing on empathy, Maptime seeks to break barriers to entry and create a more open culture in which “community, inclusivity, and accessibility” are key components for positive learning experiences. Moreover, Pete Masters, coordinator of Missing Maps, described the driving forces for mass volunteer engagement – motivation and context. The spark driving the increase in engagement is not mapping or OSM, but a commitment and desire to contribute to the humanitarian cause. For Tyler Radford, Interim Executive Director of HOT, “mapping is about the people and process as well as the product.”

HOT in the Ebola response

During a panel discussion on the humanitarian response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, representatives from the CDC, HIU, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), British Red Cross, and HOT discussed the role of spatial data in OSM in their respective organization’s response to Ebola, the challenges and benefits of working with HOT, and ways to build upon existing foundations to best assist the workers in the field. The discussions shed light onto the values and challenges of using OSM in the field, such as:

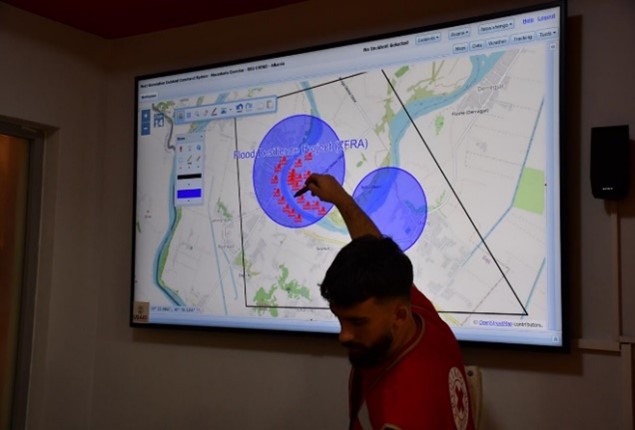

- In the response to the Ebola outbreak, OSM has functioned as a valuable piece of health infrastructure. In a successful example, GIS aided field health workers in their contact tracing and monitoring of cases. Nigeria’s preventative efforts and overall aggressive approach towards contact tracing led to its relatively rapid eradication of the virus.

- HOT succeeds when the data it generates allows operational decision-makers in the humanitarian field to allocate resources more effectively. There are immense amounts and types of data yet to be collected in order to best serve vulnerable populations in high-risk states.

- Responders utilizing OSM in the field frequently ran into questions regarding administrative units and boundary issues. Volunteer mappers working from satellite imagery cannot easily collect localized knowledge. Coordination with local institutions and engagement with rural communities will be necessary to get to the local level of determining critical characteristics.

- Major institutions are increasingly moving towards the “serious utilization of OSM” in their field work. And though the effect is felt throughout the decision-making process, the awareness surrounding OSM’s unique impact remains relatively low among senior leadership. Although large institutions typically require time to build inertia and adopt new technologies, initiatives from HIU, namely Imagery to the Crowd (IttC) and MapGive, are bridging the gap between high-level decision-makers and partners and the grassroots-based communities producing crowdsourced maps.

- In July 2014, MSF published a case study, “GIS Support for the MSF Ebola response in Guinea in 2014” which documents the role of a GIS officer in the field, as well as the unique benefits and outputs of GIS operations. The report is a rare example of much-needed documentation and tangible evidence of the real impact of GIS work in humanitarian operations. More examples such as this serves to advance the agenda of geographic data and crowdsourced maps as a cogent resource for emergency response.

Beneficiary communication members of a Liberian Red Cross Safe & Dignified Burial (SDB) team record data using mobile phones, which allows for later analysis and mapping of cases. Source: Victor Lacken/IFRC

The way forward

Collaborative discussions will continue on OSM and the HOT community, including scaling, monitoring performance, improving validation tools, and sustaining engagement. In addition, the HOT community has yet to effectively leverage the immense skills of non-mappers, particularly in areas like advocacy, university partnerships, marketing and communication, and language translation skills. Ian Schuler, CEO of Development Seed, raised the broader issue of coordination with the humanitarian response community. As a piece of “critical infrastructure for emergency response,” Schuler states that HOT must go beyond the single user of the OSM community “by refocusing efforts to create a more diverse ‘digital ecosystem’ that will increase user-ship and engagement among different actors from various cultures.”

In discussing the way forward, John Crowley of the UN Global Pulse posed other key questions concerning future design challenges, operations and decision-making, and community engagement. For Crowley, “the answers depend on the individual mapper, whose work is a voice in international dynamics that is shaping the humanitarian world.” Crowley spoke of HOT’s “great and growing responsibility to grow its capability to meet the challenges in the world before us.” In closing, he left the following pieces of advice: i) Festina lente – “Make haste slowly,” ii) understand compromise, and iii) continue the work of extending local knowledge.

Click the following links to contribute and find resources on Crowdsourcing and Crisis Mapping.

Click here for access to many of the tools and resources that the American Red Cross GIS team uses to organize and accomplish its work.

Lessons Learned :

Supporting Materials :