How to create effective and inclusive early warnings: 11 recommendations from research

Early warning systems (EWS) have been widely recognized as an essential tool to reduce risks and improve preparedness and response to natural hazards. To be effective, EWS must go beyond the mere dissemination of alerts and encompass multiple elements – from increasing the population's risk knowledge to building response capabilities.

To address the key aspects of warnings, the UCL Warning Research Centre (WRC), supported by the Global Disaster Preparedness Center/IFRC and the Anticipation Hub, has prepared a series of Warning Briefing Notes. Each Briefing Note analyzes the current state of a specific element of early warning and highlights key challenges, showcases examples, and provides recommendations for those working on policy and practice. This article summarizes the main findings of the series. For more in-depth information and recommendations on the topic, please refer the Briefing Notes.

Effective warnings result from a long-term process of creating understanding and action

The effectiveness of warnings can be limited if people do not understand or trust the messages being conveyed, or if they are unable to act on them. To overcome this, warning systems should extend beyond message dissemination and be viewed as long-term social processes that involve integrated systems of preparedness, vulnerability analysis and reduction, hazard monitoring and forecasting, disaster risk assessment, and communication.

This process should include the 3 E’s (Education, Exchange, Engagement) to help create understanding and the 3 I’s (Imagination, Initiative, Integration) to create action. This approach needs to be enacted long before a disaster strikes so that the affected people know what to expect, believe the messages, and act on them.

To enhance warning systems, it is essential to develop warnings that consider and integrate multiple hazards and vulnerabilities. It is also important to create mechanisms to overcome silos and territorialism and adopt public engagement and outreach programs to help people identify and fulfill their needs for enhancing preparedness and response behaviors and actions.

Society’s diversity should always be considered in warning processes

Inclusive warnings help ensure that everyone, regardless of their characteristics or abilities, can receive and act on hazard-related information. Designing inclusive warnings involves tailoring them to the needs of all people, not just the majority, and taking into account characteristics such as sex, gender, age, abilities, belief systems, languages, and so on. Using a single technology or mode of communication may exclude some people, so warnings should cover a variety of methods, messaging, exchanging, and formats.

Inclusive warnings should connect all governance levels, including local, national, and international, and cover a range of timeframes and spatial coverage. By ensuring that everyone can receive and act timely on hazard-related information, inclusive warnings facilitate early action and anticipatory action, which will also contribute to reducing inequalities and inequities across society.

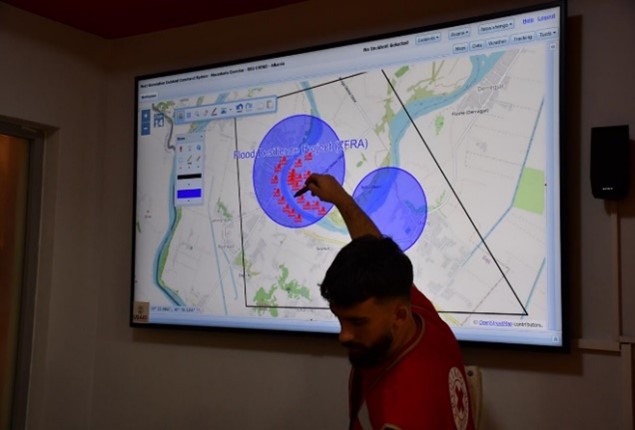

Community-based EWS bridge crucial gaps in providing early warning for all

Community-based early warning systems (CBEWS) provide community members with critical information to assess their risks and make decisions to protect their lives and livelihoods. These systems are developed and implemented at the community level, which sets them apart from national scale early warning systems. CBEWS are essential for achieving "early warning for all" because they address the gaps in coverage of national early warning systems, which often leave communities especially vulnerable to hazards due to insufficient infrastructure and resources.

CBEWS prioritize community empowerment and ownership throughout the process, working closely with community members to assess the hazards they face, identify the factors that affect their vulnerability, and determine their capacities to respond to these risks. This emphasis on community ownership is critical to ensuring the long-term sustainability of CBEWS, allowing the system to adapt and evolve over time to meet changing needs.

To be effective, CBEWS must be integrated into existing community systems – formal and informal – that are already working to identify risks and/or share information. For CBEWS to be truly participatory and community-based, they must be inclusive of diverse people and groups, particularly those affected by social inequalities and marginalization who oftentimes are the most vulnerable to hazards.

Impact-based early warnings empower vulnerable communities to reduce risks

In recent years, national meteorological and hydrological services have made significant progress in forecasting weather-induced events with greater accuracy and precision. But simply providing timely warnings is not enough to guarantee that people will understand the message and take appropriate action. Impact-based EWS (IB-EWS) help close existing communication gaps by communicating on 'what the weather will do', the expected damages and the clear guidelines on what citizens and authorities can do to reduce their risk.

If communities are expected to implement IB-EWS, they need guidance to exploit their local risk knowledge to develop a system within their capabilities. For this purpose, the Site-Specific EWS (SS-EWS) framework has been developed by the Polytechnic University of Catalonia to guide vulnerable communities in designing and implementing community-based IB-EWS using local risk knowledge and resources. Ultimately, SS-EWS helps ensure that communities are at the center of any people-centered IB-EWS design and implementation, promoting effective risk communication and appropriate anticipatory protective actions to reduce risk during emergencies.

First Mile of Warnings: Involving affected people in warning development improves trust and effectiveness

People using warnings should be involved in the warning design and implementation from the beginning to build trust, credibility, and effectiveness. Understanding the meaning of warning messages and choices for action cannot start when a danger appears. Instead, it requires integrating the warning process into people’s lives and livelihoods by working with them to understand their resources, abilities, needs, and limitations. Collaborating with people in this manner is the first mile of warnings.

The first mile of warnings means combining formal and informal communication and information exchange modes and methods, decision-making, and implementation. Providing technology to disseminate information does not constitute the first step in a warning. Rather, it is the connection between local and external knowledge and experiences that achieves the first mile. Furthermore, the first mile recognizes that people are not passive recipients of messages and data, and they want to be involved in their own warnings and choices for actions.

Core local systems must be at the center of warning in conflict-affected areas

Co-production of warning messages together with communities is an effective approach to developing warnings, but it becomes more complex in contexts with violence and conflict, requiring engagement with people and institutions that may be in conflict with each other. There is a need for policies and best practices that are tailored to these contexts, with warnings developed around core local systems that are essential for meeting basic needs – such as those involved in the provision of supplies, shelter, and social support – before, during, and after disasters.

These core local systems can also play essential roles in the development and management of disaster risk reduction, preparedness, and response capacities tied to warnings. Engagement strategies should assess how violence and conflict limit the delivery of services and leverage core local systems for two-way communication with hard-to-reach groups. Overall, developing and implementing early warning systems in conflict-affected areas requires an approach that prioritizes people and their core local systems.

Explaining near misses and false alarms helps enhance public trust in warnings

False alarms and near misses can hinder public trust in warning systems, leading to complacency and reduced preparedness for real risks. Weather agencies, in particular, face the challenge of communicating probabilistic forecasts that are rarely 100% certain. To address this issue, transparency and communication are key, including the use of uncertainty information in hazard warnings and explanations for why false alarms and near misses occur.

Agencies should define false alarm ratios and rates as part of performance metrics and tell the public what is not known about a possible threat, as well as what is known. False alarms and near misses can serve as an opportunity to improve public hazard awareness and risk appraisal if they are used as an educational tool for both the public and authorities.

Overall, the goal is to reduce confusion between false alarms and near misses and to enhance credibility and public engagement. This includes defining key terms, using uncertainty information, and explaining why some warnings may result in false alarms. By doing so, agencies can improve the effectiveness of their warning systems and mitigate the risk of complacency among the public.

Adopting CAP helps ensure that public alerts are consistent and easy to understand

The common alerting protocol (CAP) offers a simple, open, and consistent format for all types of emergency alerts and public warnings over all networks and warning systems. As an International Telecommunication Union (ITU) recommended standard, it is a globally used and not limited to any particular application or communication method. CAP can reduce costs and complexity by eliminating the need for multiple custom software interfaces and enabling the integration of actionable guidance directly into an alert. It also ensures consistency in information transmitted over numerous delivery systems and normalizes warnings from various sources.

CAP provides a template for effective warning messages based on best practices and facilitates situational awareness, pattern detection, and data analysis. The format is compatible with existing and emerging communication formats and techniques, allowing for a single input to activate all types of alerting and public warning systems, including for cell broadcasting and location-based SMS to quickly reach people in at-risk areas.

Cell broadcast and location-based SMS have proven effective for alerting

With 3 out of 4 people owning a mobile phone (as of 2022), mobile networks have become a powerful communication channel to alert populations about imminent hazards. Location-based SMS and cell-broadcast are two proven technologies that can send warnings to those located in an at-risk area. Combining both cell-broadcast and location-based SMS is recommended as they have different advantages and shortcomings, making them an ideal solution when countries have the necessary financial resources and expertise.

However, many countries have yet to implement a mobile-based Early Warning System (EWS), and it is recommended that governments, emergency managers, telecommunications workers, donors, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations work together with EWS experts, mobile network operators, and software companies to accelerate the rollout of EWSs. Clear regulatory frameworks and appropriate incentives can accelerate the rollout of mobile-based EWSs, and regular tests and awareness campaigns can prepare the population and increase their trust in the system.

A systematic and bottom-up approach is key to effective landslide EWS

To create effective Landslide Early Warning Systems (LEWS), it is crucial to involve the target community in the planning, elaboration, and implementation of the various components. It requires a systematic approach and proper synergy between technical and social know-hows. LEWS managers need to integrate the two know-hows and propose solutions that integrate the knowledge and enable participation of local communities.

LEWS must be designed as an Anticipatory Action and follow a prospective and preventive perspective to address landslide risk reduction. When warnings are issued, the operational framework of the LEWS must be known by everyone, including people monitoring, institutional stakeholders, and residents. During emergency phase, LEWS must properly address evacuation routes and emergency shelters.

Infectious disease warnings need to work across sectors to lead to earlier prevention

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), including COVID-19, are driven by social and environmental factors and have been rising for the last 60 years. Even though the need for integration across disciplines is clear, many warning systems for these diseases fail to monitor and include animal and environmental health data in their risk assessments.

To be effective, infectious disease warnings need to address the complete picture and contexts of the emergence of infectious diseases. They need to integrate natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities in their design and risk assessments, as well as action mechanisms. Multi-sectoral integration will support them to switch from a responsive approach that waits for the disease to reach the population before starting to monitor the risk, to an anticipatory approach that maps and addresses the many, varied social and environmental drivers of these diseases, helping to safeguard human, animal, and environmental health.