Beyond Individual Risk: Why Extreme Heat Demands a Systems Response

At a Glance

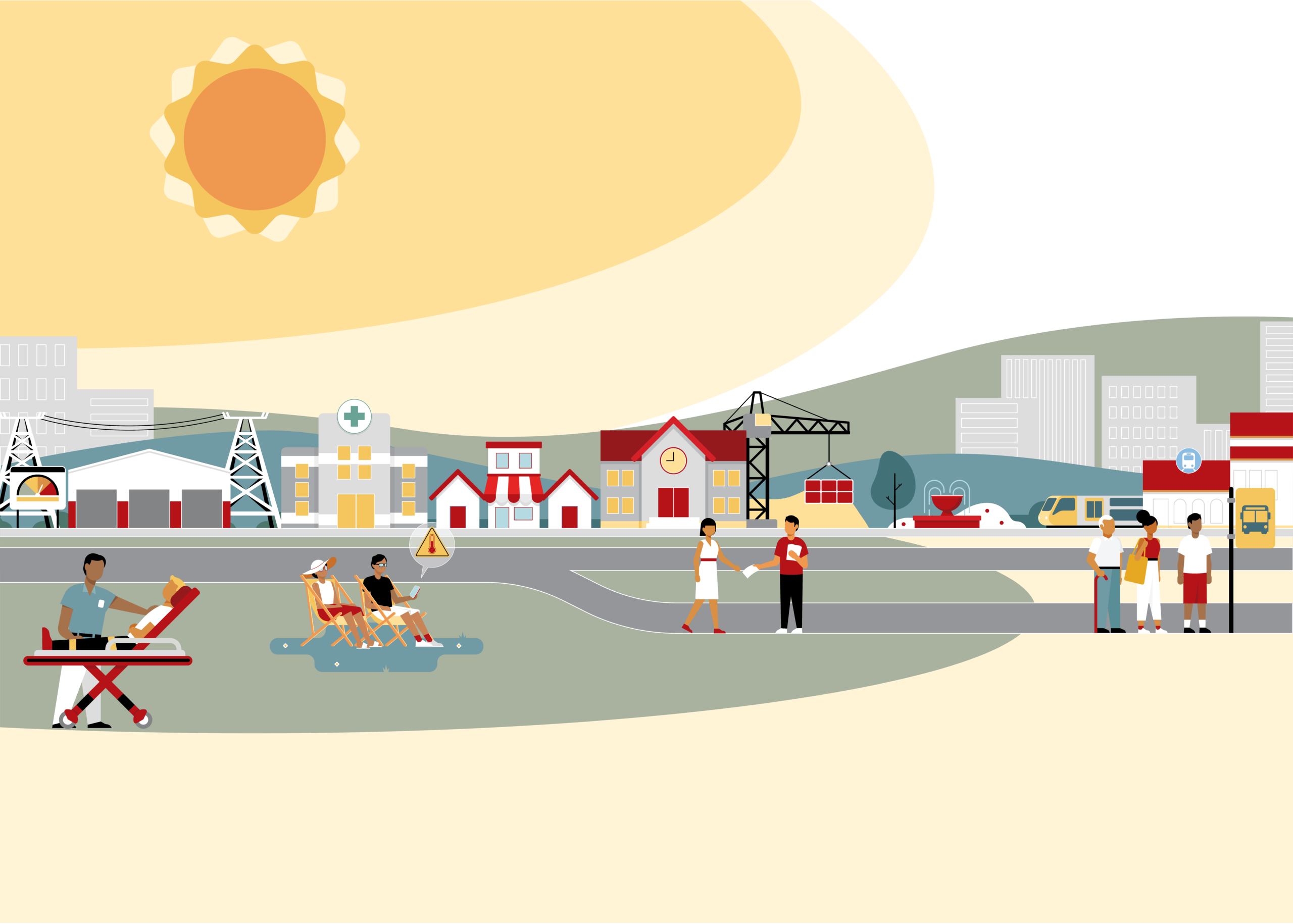

- Extreme heat becomes a disaster when it overwhelms the systems people rely on — housing, health, infrastructure, ecosystems, and social services.

- Heat impacts do not occur in isolation but often cascade across sectors. Disruptions in one system (especially energy and critical infrastructure) can quickly trigger failures in others, amplifying harm and disruption.

- Reducing heat risk requires systems-wide resilience, including inclusive planning that addresses inequality, exposure, and access to services — not just individual behaviour change.

Extreme heat is the deadliest climate hazard in Australia, causing more deaths than all other natural hazards combined . Yet it remains under-recognised as a disaster risk and is often treated as an individual inconvenience rather than a collective challenge.

“Heat is a silent killer. You can see a cyclone or a fire, but heat is invisible, and its impacts often occur after the event. I’ve seen hospital admissions rise days or even weeks later, while the number of people living rough and vulnerable communities continues to grow,” notes a government agency representative.

New applied research using the Post-Event Review Capability (PERC) — a systematic methodology for examining disaster events to capture learnings for strengthening future resilience — reframes how we understand extreme heat. This first-ever PERC on extreme heat, delivered collaboratively by Australian Red Cross (ARC), Zurich Australia, ISET-International, Monash University, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the Z Zurich Foundation, with support from the Zurich Insurance Group, examines extreme heat events in Adelaide, South Australia across the 2024-2025 Summer. One of its central findings is clear: extreme heat becomes a disaster when it overwhelms the systems people depend on. Resilience therefore must be built at the systems level — not only at the level of individual behaviour.

How Heat Impacts Cascade Across Essential Systems

Extreme heat does not only affect people at the individual level — it also strains the infrastructure and services that people rely on for health and safety. Extreme heat amplifies existing pressures across housing, health, infrastructure, and social services, with disruptions in one area often worsening impacts in another. When these systems are already stretched, extreme heat can push them beyond safe limits, turning a climate hazard into a systemic crisis. The sections below outline key risks and impacts across major sectors, along with practical entry points to strengthen resilience.

Energy and other critical infrastructure represent one of the most significant sources of cascading risk. During extreme heat, electricity demand spikes while transmission lines lose efficiency and transformers overheat. Power failures then cascade across systems, disrupting cooling, water provision, transport, communications, and healthcare. Strengthening power system resilience and planning for continuity of critical services are foundational to reducing systemic heat risk.

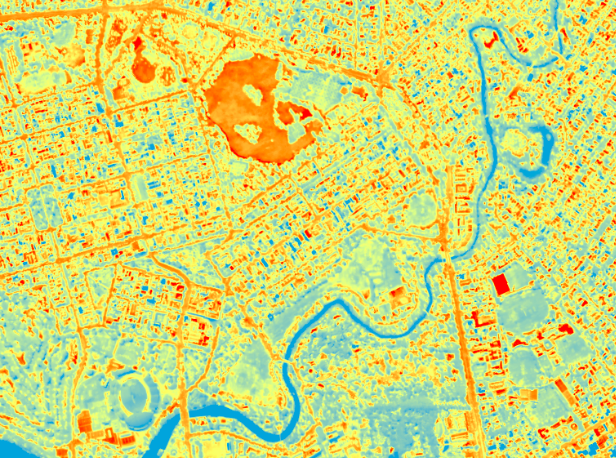

Housing and urban development play a critical role in determining heat exposure. Poorly insulated housing, degraded materials, failing roofs and insulation, and overloaded cooling systems can quickly lead to unsafe indoor temperatures. These risks are intensified by urban design, where dense development and hard surfaces trap heat and limit overnight cooling. Strengthening resilience requires heat-informed urban planning, climate-resilient building codes, and retrofitting existing housing to support passive cooling.

Urban greening and the natural environment are equally central. Extreme heat pushes ecosystems beyond thermal limits, reducing tree canopy, degrading habitats, and warming and deoxygenating water bodies. As these natural systems weaken, communities lose essential cooling and protective functions. Increasing urban tree cover, integrating green and blue spaces into development, and protecting heat-resilient ecosystems are therefore core resilience measures.

Health systems sit at the frontline of heat impacts. Heat stress, dehydration, worsening air quality, and exacerbation of existing conditions increase morbidity and mortality. At the same time, healthcare facilities often face demand surges while coping with power outages, equipment failure, or unsafe indoor conditions. Building resilience means embedding heat risk into healthcare planning, strengthening data on heat-related illness and death, integrating social protection, and addressing the mental health impacts of prolonged heat exposure.

Extreme heat also exposes and amplifies existing inequalities. The safety of at-risk populations is shaped by how exposure, vulnerability, and capacity intersect. Older people, outdoor workers, people with chronic illness, and those without access to reliable cooling face disproportionate risk. When vulnerabilities are unrecognized or heat warnings do not reach the right people, impacts escalate rapidly. Identifying at-risk populations, planning inclusive extreme heat responses, activating cool spaces, and tailoring communication are critical entry points for reducing preventable harm.

Red Cross TeleRedi Program

TeleRedi is a phone support service that checks in on vulnerable people, especially those who are isolated during extreme heat events. Before each Summer, Australian Red Cross confirms details and emergency plans with registered participants. During extreme heat events, trained volunteers check on wellbeing and escalate concerns to emergency contacts or ambulance services if needed.

Heat impacts on workplaces and schools are similar, and significant. Extreme heat makes outdoor and poorly ventilated work unsafe, undermining livelihoods and reducing productivity. Education is disrupted when heat affects sleep and concentration, when classrooms become unsafe, or when power and cooling systems fail. Integrating heat risk into workplace safety standards, adjusting schedules, and ensuring schools are heat-safe environments are essential for social and economic continuity.

“There is no way I could work for two weeks straight in 35°C. It’s the cumulative effect — dehydration, lack of sleep — while still being expected to get the work done,” explains a parks and gardens supervisor.

Despite these widespread impacts, heat is often not fully integrated into disaster management systems. Unlike sudden-onset hazards, heat rarely has universal and clear triggers that define when it becomes dangerous. Without impact-based forecasting and tailored warnings, escalating risk can go unnoticed — particularly during compound events such as heat combined with bushfire or storms, when impacts interact rather than simply add up.

Finally, community awareness and cultural norms shape how all of these systems function. In Australia, heat is often normalised as “business as usual,” discouraging early action and collective responsibility. When heat is framed as an individual problem, societal risk increases — resulting in higher mortality, economic disruption, interrupted education, and overloaded systems.

“When we talk about dangerous heat, a huge part of the population switches off. Toughing it out is a source of national pride,” reflects a medical specialist and academic.

Extreme heat is not a single hazard with isolated impacts. It is a systemic risk that interacts with infrastructure, institutions, ecosystems, and social norms. This PERC demonstrates that reducing heat risk requires strengthening the systems that underpin everyday life.

Urban Climate Resilience Program (UCRP): A Systems Approach in Action

The UCRP brings together global actors including IFRC, ICLEI, C40 Cities, R-Cities and Plan International to strengthen urban climate resilience in nine countries. Powered by the Z Zurich Foundation, Australian Red Cross (ARC) and Zurich Australia lead UCRP in Western Sydney.

Over the past three years, the UCRP has demonstrated how a systems approach to extreme heat can translate into tangible resilience outcomes across communities, services, and decision-making spaces. Through layered community engagement and policy influence, the UCRP has addressed heat risk across critical systems. UCRP supported the launch of the inaugural Extreme Heat Awareness Day in 2025. Within two years, the initiative reached millions nationwide, helping to shift community awareness and cultural norms by reframing extreme heat as disasters that require anticipatory action. This shift has been reinforced through Extreme Heat Preparedness Workshops, RediCommunities initiative and the First Aid for Summer course, which supports the safety of at-risk populations by reducing barriers to vital health care. In parallel, UCRP has influenced disaster management decision-making by embedding community evidence into policy processes, including through the Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils’ Heatwave Taskforce.

Explore the systems level impacts and entry points for extreme heat resilience via the Extreme Heat PERC reports — Heat stress at work, Understanding extreme heat and entry points for action, and Strengthening resilience to extreme heat: an Adelaide case study — which offers practical insights for practitioners and decision-makers working to build resilience in the face of extreme heat.

Authors: Eilish Maguire, Senior Officer - Resilience, Australian Red Cross; Dr Karen MacClune, Executive Director, ISET-International; Atalie Pestalozzi, MERL, Research & Graphic Design Specialist, ISET-International; Dr Rachel Norton, Knowledge & Learning Specialist, ISET-International; Dr Adriana Keating, Research Fellow, Monash University ; Sita Hitchcox, Sustainability Lead, Zurich Financial Services Australia

Edited: Cale Johnstone, Vladislav Kavaleuski