Building a Disaster Preparedness Campaign from the Ground Up: A Case Study from Greater New York

One day Denise walked through my door and wanted to speak to me about volunteering in disaster preparedness. As we chatted, I found out that she was a registered nurse at a local New York City hospital in the Burn Center. Most patients who are admitted suffer from devastating burns across their body and are immigrants who speak little English. As a result of this, Denise was motivated to get involved with the Red Cross to work on fire prevention. I was moved by her story and it speaks of a great need to re-invigorate the work of emergency preparedness in the region and to focus on often overlooked communities.

When I was first hired to lead regional preparedness for the Greater New York region 6 months ago, I was confronted with the challenge of building a new department from the ground up. Moreover, the American Red Cross had just entered in a partnership with New York State and the Governor’s office to deliver disaster preparedness education to communities by the end of March 31, 2015. I needed to move quickly and build a daily operation that would mobilize volunteers to go out into communities and train 7,429 people in six months.

When I started I had no volunteers, no centralized workspace, and a pile of boxes leftover from the last incarnation of the department. It was a typical political campaign scenario. I knew immediately that I needed to create a compelling reason to recruit and mobilize volunteers to join this campaign. After a quick assessment of the challenges facing each chapter through the region, I began studying the Obama 2008 and 2012 political campaigns for inspiration about running a successful volunteer campaign.

Principle 1: Building Human Infrastructure for Preparedness

In adopting a political campaign model to run a preparedness program, I aimed to scale up an operation of one staff member to a regional machine with localized community teams. This model borrowed much from the “snowflake” model of community organization. Obama 2012 trained and leveraged volunteer coordinators and neighborhood leaders to oversee geographic territories and to ensure community outreach. This snowflake model of organization ensured total geographic coverage.

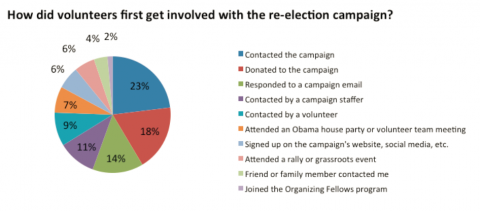

Another important element of scale is that I needed to be in a never-ending state of volunteer recruitment. The Obama 2012 campaign recruited 51% of its volunteer workforce through active recruitment. Through word of mouth, committed campaign volunteers helped attract new committed volunteers through social networks. It is important to note that Obama, as the incumbent president, already had brand recognition, which helped draw volunteers to the campaign. I found myself traveling the region and giving “stump speeches.” The goal of the stump speech was to galvanize attention and support from existing Red Cross volunteers and to sway new volunteers to join the preparedness department and embark on a high-intensity preparedness campaign with a tight deadline.

Active vs. Passive Recruitment: Obama 2012 Campaign

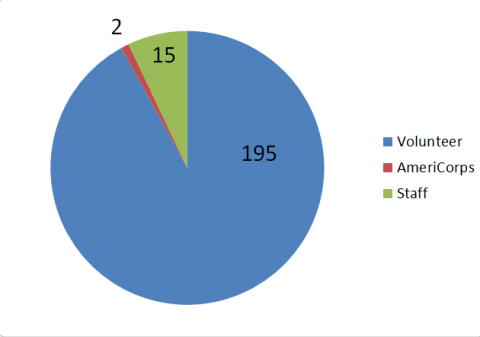

Through active recruitment of volunteers, I was able to grow the department from zero to 30 active volunteers that formed the core operations for the duration of the campaign. The result is that the success of the Governor’s Preparedness Campaign has been empowering a team of volunteers to run the operation. The breakdown of the events taught throughout the campaign illustrates that this has been a volunteer-led operation from the beginning.

Events Taught – Workforce Breakdown

Principle 2: Finding Audiences Among Unreached Communities and Unspoken Languages

One of the major strategies during Obama 2012 was that the campaign tapped into a voting base that was not politically active by registering them to vote for the first time. When I was first hired, the American Red Cross primarily did disaster preparedness presentations in English. This reflected the fact that preparedness programming leaned heavily toward English speakers. One of my first goals was to tap into the power of my volunteer base to deliver the message of preparedness to their own communities in a multitude of tongues.

The greatest challenge to preparedness work in New York City is the sheer amount of people, with a diversity of cultures and languages, in constant movement. Every day people from all over the world come to Manhattan to visit or to work. Although the island of Manhattan has about 1.5 million residents, the daytime population of Manhattan surges to 4 million people every day.[1] This daily migration reminds us that people have always moved across borders since time immemorial. As such, disaster risk reduction and resiliency efforts should match this dynamism, as opposed to focusing on a bounded geographical region.

Every day, I work with volunteers with amazing stories that illustrate the power of the global Red Cross/Red Crescent movements. Their commitment to humanitarian values comes with them wherever they may live. Andrea, a new volunteer in my department, reflects this migration. While growing up in Colombia, she witnessed the work of the Red Cross/Red Crescent. This memory carried with her as she moved to the United States of America. After witnessing the regional impacts from Hurricane Sandy, she once again saw the power of the RC/RC movement and decided to volunteer. Andrea’s story is a common one for the Greater New York chapter of the Red Cross, where numerous volunteers are foreign born and may have volunteered for a local Red Cross branch in their home countries before immigrating to the United States. The diversity of my volunteer base has allowed me to deliver disaster preparedness in English, Spanish, Haitian Creole, Fulani, Ewe, Mandarin, and Cantonese.

Principle 3: Using Data Collection and Mapping to Guide Program Strategy

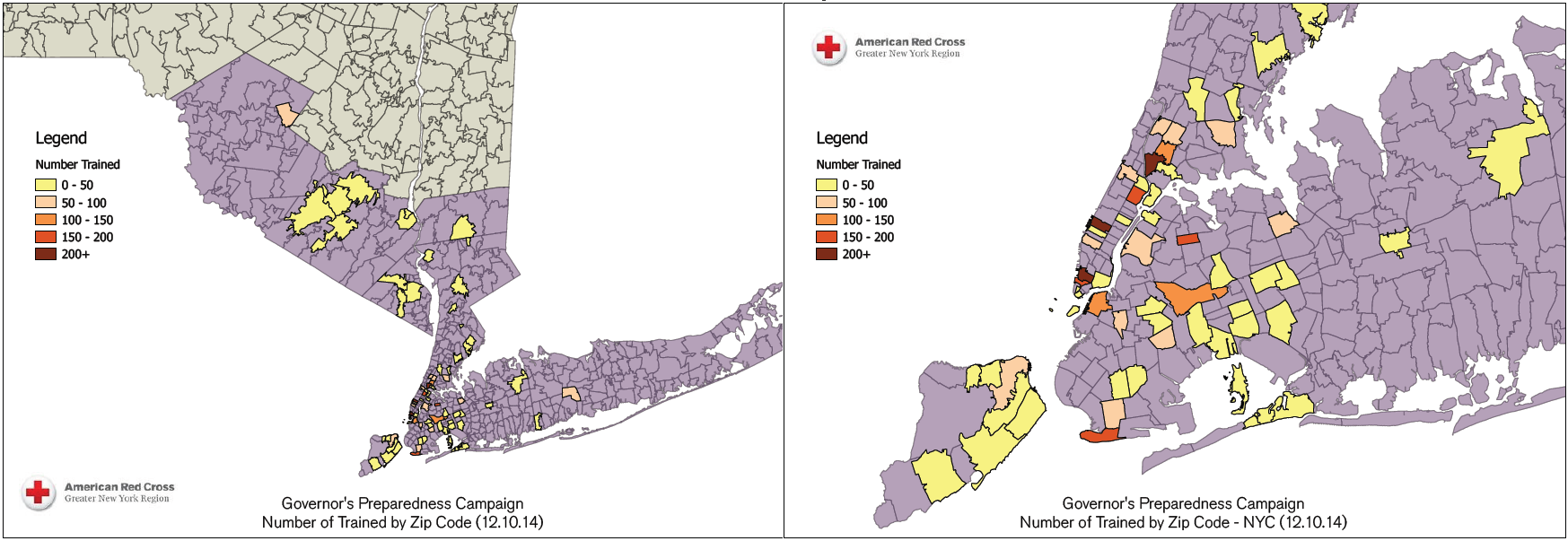

One of the biggest reasons Obama 2012 was a successful political campaign was their attention to data to generate insight and guide campaign decision making. As the sole staff member for a region of 13 million people, I am often faced with the constraint of time. How can I reach out to the right volunteers who would be more likely to teach preparedness presentations in their own neighborhoods? My team created many tools using databases and mapping software to better align trained presenters with community events. Careful collection and analysis of data helped make a small team far more efficient and effective. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) became a valuable tool to understand communities that we have not been able to reach out to and how we could improve our efforts.

Home Fire Preparedness Campaign: Moving into Disaster Risk Reduction

The Individual & Community Preparedness Department has just achieved our regional target of training over 7,000 New Yorkers in emergency preparedness two months ahead of schedule. As we wrap up the operations for the Governor’s Preparedness Campaign, we have seen how following these three principles enabled us to build a large volunteer driven operation that led success in a little over five months. This insight will help guide us as we launch our current disaster preparedness program: the Home Fire Preparedness Campaign, a national five-year effort focused on installing smoke alarms and disaster risk reduction.

Lessons Learned :

Supporting Materials :