Migrant Protection, Gender and Inclusion

Overview of Protection, Gender and Inclusion

The Red Cross Red Crescent Movement adopts the InterAgency Standing Committee’s definition of “Protection” as “all activities aimed at obtaining full respect for the rights of the individual in accordance with the letter and the spirit of the relevant bodies of law (i.e. Human Rights Law, International Humanitarian Law, Refugee law)”.

Protection in humanitarian action aims to ensure the rights of individuals are respected and to preserve the safety, physical integrity, and dignity of affected people.

Protection, Gender, and Inclusion (PGI) Approach

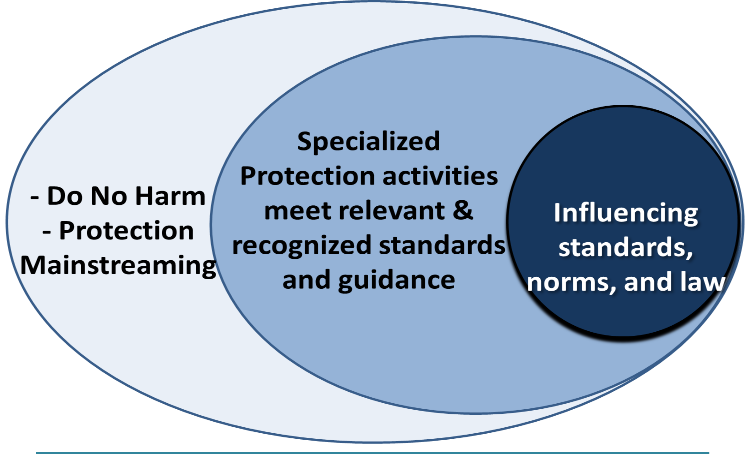

In line with the Movement Framework on Protection, “PGI” also describes an overarching approach which includes:

It also has both internal and external aspects:

- Internally, it refers to ensuring that the actions of the Movement respect, and do not endanger the dignity, safety, and rights of persons.

- Externally, it refers to action intended to ensure that authorities and other actors respect their obligations and the rights of individuals.

The interrelation between each of these elements is illustrated in the diagram of the Movement on the right.

1. Protection Mainstreaming

HSPs should use the Minimum Standards on Protection, Gender, and Inclusion to ensure Dignity, Access, Protection, and Safety (DAPS) for people using their services.

These minimum standards include specific sector-by-sector guidance on how to ensure DAPS in all services. Application of minimum standards may need some contextual adaptation, but the principles behind the standards apply in any context. To ensure a coherent Movement approach, in contexts where ICRC is also present, make contact with the ICRC delegation’s protection teams.

Ensure all operations, approaches and staff provide a safe environment and avoid inadvertently causing harm. Such harm might be physical or the safety and dignity of service use and could include psychological harm.

Conduct a detailed risk analysis of potential harms that could occur and mitigate risk wherever possible.

Take into account the specific needs and barriers faced by different groups. This includes, but is not limited to:

- women and girls,

- children,

- people with disabilities,

- and people from sexual and gender minority groups.

Some factors exacerbating vulnerability

- Irregular status or lack of documentation

- Age – children, adolescents and older people may all have age-specific vulnerabilities;

- Disability or mental health problems, including as a result of experiencing or witnessing violence during migration;

- Family separation and, for children, being separated or unaccompanied;

- People from sexual and gender minorities;

- Criminalisation due to crimes committed in country of origin or migration status;

- Loss of resilience, particularly after multiple migration attempts, forced returns or push-backs.

Risks Migrants Face:

- Being caught up in/controlled by trafficking or smugglers’ networks, or recruited by armed groups or exploitative Quranic schools (e.g. talibé children);

- Involvement in sex work/prostitution or forced marriage;

- Exploitative or abusive labour, child labour, debt bondage;

- Violence, including sexual violence;

- Physical risk, e.g. heat, cold, unsafe transport, etc.

- Denial of rights/lack of access to services/legal assistance

- Detention, including child detention with adults or inappropriate care;

- Forced returns or push-backs.

- Sexual Exploitation and Abuse.

2. Specialised protection interventions

Child protection

In 2019, 37.9 million people under the age of 20 were on the move, and child migrants accounted for 12% of the total migrant population. In recent years the number of unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) has been growing, and In 2017 it was estimated that at least 300,000 unaccompanied and separated child migrants were in transit in 80 countries – a five-fold increase from five years earlier.

Children and young people on the move face the same risks as adults, but are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, particularly when unaccompanied or separated.

Children are also put at greater risk by policies that:

- separate families or make the family reunion more difficult,

- provide assistance poorly adapted to their needs,

- by institutionalization or detention

- and by loss of opportunity and access to education.

Girls and boys will face different risks and have different needs, and children with disabilities are particularly vulnerable.

Child-friendly spaces (CFS) should be an integral part of an HSP, as a temporary refuge and breathing space for children.

Facts about a CFS:

- Provides a safe place where children can meet other children to play

- Helps children learn to deal with the risks they face

- A place for educational activities

- Safe to relax

- Can be set up quickly in virtually any location

- Provide temporary respite from the migration route

- Act as an entry point for formal education and integration

HSPs can also play an important role in child protection by providing safe spaces for children and lactating mothers, by:

- Promoting their physical and psychosocial well-being,

- Ensuring access to first aid and medical care, and life skills.

There are often particular safeguards for unaccompanied children on the move that may result in them being taken into care. This can be extremely traumatic for children, particularly if they are expecting to be united with family members further along their route. In addition, in some countries, there is a risk that the solution may cause more harm than the problem – for example, if care is inadequate or inappropriate, if children end up being deprived of their freedom for a prolonged period of time, or if they are held with adults.

Since migrants often find themselves in poorer areas, it is worth also considering whether local children have access to safe spaces or toys and equipment to play. If not, you may want to consider making safe spaces and play areas available to the local community, ensuring recreational kits are available to each age group. This can improve community acceptance of the HSP, and facilitate integration and social cohesion.

A full toolkit on child-friendly spaces including set-up, activities, safeguarding guidelines, and training for staff and volunteers is available at the Child-friendly spaces pages of the IFRC Psychosocial Centre.

Key Resources on Child Protection

Policies

Tools and Resources

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

Sexual and gender-based violence is an umbrella term for any harmful act that results in or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to a person on the basis of their gender. (Read more: Unseen, unheard: Gender-based violence in disasters)

It is rooted in gender inequality and is an abuse of power. Because most societies are male-dominated women and girls are most often affected. All women and girls and sexual and gender minorities face discrimination, but not all experience oppression and inequality in the same ways.

SGBV can take many forms and affects people at all stages of life.

- sexual violence,

- intimate partner violence,

- trafficking,

- forced or child marriage,

- forced prostitution,

- differential access to food and services,

- sexual exploitation and abuse,

- denial of resources, opportunities, and services,

- female genital mutilation/cutting,

- sexual harassment, and

- honour killing.

HSPs should draw on specialist support to ensure they provide adequate and appropriate assistance.

Children who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning/queer (LGBTQ) may be at even higher risk, with no place of safety given often low levels of cultural and familial tolerance and acceptance. People with disabilities are also particularly vulnerable to SGBV.

It is important to be aware that migrants – and particularly those with irregular status, may have difficulty accessing existing SGBV services due to lack of information or restrictive eligibility criteria.

For example, shelters may not be open to non-nationals, or services may be targeted to specific groups – refugees, for example – and not able to accommodate people who fall outside of it.

Children, particularly unaccompanied and separated children, may be particularly at risk of sexual violence.

- All staff and volunteers should be trained on SGBV core concepts and safe referrals, and be familiar with the SGBV referral pathway available. If SGBV services are not available in the area, ensure information about related basic services is available.

- Staff and volunteers must be trained on PSEA and have signed a code of conduct.

- Staff and volunteers should download the GBV pocket guide on their mobile phones, and access the IFRC online briefing on handling SGBV disclosure. You may also want to use or refer staff and volunteers to this video by the Global Shelter Cluster on responding to a disclosure of an SGBV incident.

- Women should make up half of staff and volunteers working at an HSP, and services delivered to women and girls should be delivered by female staff wherever possible.

- Staff and volunteers should be aware that men and boys, particularly members of sexual and gender minority groups, can also experience SGBV.

- Premises should be secure and well-lit, and spaces such as toilets, showers, and changing areas should be separated by sex. Ideally, provide at least one accessible toilet/shower for people with disabilities and also as a non-gendered space. Toilets and showers must have locks.

- Make it clear through signs on the wall and in any welcome talk that the HSP is a non-violent space. Intimate partner violence and physical disciplining of children (e.g. spanking) are not acceptable.

Key Resources on Sexual and gender-based violence

Migrants with Disabilities

HSPs should ensure that all spaces are accessible to people with disabilities, or that there is a way to relocate key services so they can be accessed by people with disabilities.

Migrants with disabilities are particularly vulnerable, and their disabilities could be physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory.

People with disabilities may be less able to escape to safety in a dangerous situation while in transit and may be more vulnerable to violence and abuse. Migrants with disabilities may also feel even more powerless, and therefore more frustrated and afraid.

This can lead to increased needs for mental health and psychosocial support. This is likely to be particularly true if their disability was acquired in transit.

- Services should be adapted to the needs of people with disabilities, bearing in mind that disabilities are not always visible.

- Referral pathways should include programmes and services that may be needed by migrants with disabilities, including repair or replacement of mobility, visual or hearing aids and specialised health services

- HSPs should ensure migrants with disabilities can fully participate in the work of HSPs

- HSPs should seek their input in designing and adapting programming.

The primary objective of this tool is to facilitate the timely identification of persons with special procedural and/or reception needs. It may be used at any stage of the asylum procedure and at any stage of the reception process. This is a practical support tool for officials involved in the asylum procedure and reception and does not presuppose expert knowledge in medicine, psychology or other subjects outside the asylum procedure.

The ICRC, in collaboration with the Mexican and Central American National Societies, provides free assistance to migrants (in transit or returned) who have suffered major illnesses or injuries during their journey, including amputations, spinal cord injuries, and other injuries.

This includes the provision of prostheses and mobility aids, ambulance transfers, referral to rehabilitation and medical care centers in Mexico and Central America, reestablishment of family links when necessary.

Experience has also highlighted the importance of mental healthcare and psychosocial support. For more information on this and other initiatives, see the IFRC’s Smart Practices.

Trafficking in Persons

Trafficking in persons is a crime and grave human rights violation occurring in every country. Migrants are particularly vulnerable to trafficking, and it is an issue HSP personnel should be prepared for.

The crime of trafficking in persons has three elements:

A victim of trafficking is anyone that has been exposed to these three elements. Migrants are particularly vulnerable to being trafficked, especially because they often rely on information and support from others, to continue their journey.

Legally, smuggling is different from trafficking, though both are international crimes. But even though smuggling is often understood as a business transaction between two consenting parties, smuggling of migrants often also occurs under dangerous and degrading conditions.

It can involve coercion, fraud, or force. Smuggled migrants can become victims of trafficking in transit or on arrival in the country of destination. , They may be victims of debt bondage, in which they are required to work, often under poor and dangerous conditions, to pay off the debt or loan they have taken to make the journey.

Trafficked migrants face multiple barriers to accessing humanitarian assistance, including fear of authorities or of their traffickers, lack of support, shame, or being prevented from seeking help.

What can be done at HSPs?

HSPs cannot provide specialist services, and support to victims of trafficking should be undertaken only with expert support and advice.

HSPs can refer using effective referral mechanisms, and provide access to a range of basic services. NS should never engage in judicial cooperation in criminal investigations.

Whatever actions are undertaken the following principles should apply:

Assistance and protection should promote person-centered support that takes into account individuals’ needs, interests, and wishes, as well as the imperative to Do No Harm to migrants and host communities. Assistance and support should be provided only with the trafficked person’s consent on an informed basis. (In safeguarding a child, prior consent of the child may not be required.)

The rights of trafficked persons should be promoted at all times, and they should receive clear and consistent information about their rights. Assistance and support should not be conditional on an individual’s cooperation in the criminal investigation.

The forms, patterns, humanitarian consequences and vulnerabilities of female and male trafficked persons will be different, and assumptions should not be made about anyone’s needs and experience. A gender-sensitive approach ensures that assistance and support address gender-based discrimination and violence, and promote gender equality and realisation of human rights for men, women, boys and girls.

The best interests of the child should guide all decisions regarding children, and activities for child victims should be age, gender and culturally sensitive. In case of doubt, a person claiming to be a child should be treated as such and benefit from all the protection measures granted to children. Support programmes targeting child victims need to be child-focused and take account of child-specific needs, including access to school and education, psychosocial support and social inclusion.

Strengthen partnerships with key stakeholders engaged in assistance and protection to trafficked persons, including national and international civil society organisations and state authorities. Respect for victims’ rights should be at the heart of these partnerships.

Every effort should be made to ensure that confidential information remains protected and that this protection is recognised in origin, transit, and countries. Confidentiality should be respected in any engagement with partners during assistance and protection.

Key resources

3. Protection Activities

There should be three levels of engagment with protection issues at HSPs:

Key protection activities in HSPs include:

Information that can help people keep safe is one of the most important services an HSP can offer. This can be anything from guidance about the risks they may face, to where services can be accessed.

The rights of trafficked persons should be promoted at all times, and they should receive clear and consistent information about their rights. Assistance and support should not be conditional on an individual’s cooperation in the criminal investigation.

Safeguarding measures protect the health, well-being and human rights of people using HSP services, especially children, young people and vulnerable adults. Safeguarding measures should be applied in every programme and activity, and referral partners should apply similar standards.

More information is in Negotiating Political and Social Space and Safeguarding.

Referral pathways should be established from the beginning, and staff should be familiar with both partners’ services and their ways of working.

For more details check this section Safe Referral.

A Humanitarian Service Point should itself be a refuge, but HSPs can also house safe spaces for particularly vulnerable groups such as women, adolescent girls and children. Safe spaces can be places to play, relax, express themselves, feel supported, and learn skills. It can give people a vital breathing space to take stock of what they have experienced and reflect on where they want to go from here. They are particularly important to migrant women and girls, who are often isolated and lacking in peer support. Safe spaces are an excellent place to provide information, confidential support, and mental health and psychosocial assistance.

Mental health and psychosocial distress can be particularly acute for children and young people, who may have witnessed violence and death, been subjected to violence and abuse, injury, or family separation, or may simply be missing home and loved ones. It will most likely be impossible to provide comprehensive mental health services for people on the move, though referral options should be available for people who are suffering from severe distress or appear to have a mental health disorder. Typically, HSPs will focus on supportive measures: psychological first aid, safe spaces, games, and activities, and RFL and family reunion. For more details, go to Mental health and psychosocial support

Avoid overreach. If you aren’t sure you can provide an activity safely, it is best not to provide it at all.

In many countries, protection activities are limited by resource shortages, insufficient capacity, and gaps in implementation. This means staff and volunteers of HSPs may detect real and urgent problems with no effective way of addressing them. Support will need to be put in place to help them manage associated stress and frustration, as well as ongoing exposure to migrants’ experience of violence, stress and loss.

Partners

Partners are a vital part of protection. This is because no one organisation can provide a full range of protection services, and also because protection issues often stretch well beyond the humanitarian sphere.

It may be useful to bring together key partners – including migrants themselves – to brainstorm about who should be engaged in order to improve protection and referral.

Potential partners

- Law enforcement actors

- Border officials

- Ministries of social, women’s, children’s, or family affairs

- Local government

- Other identified humanitarian actors involved in other response work